Travelling Through Art

Written by

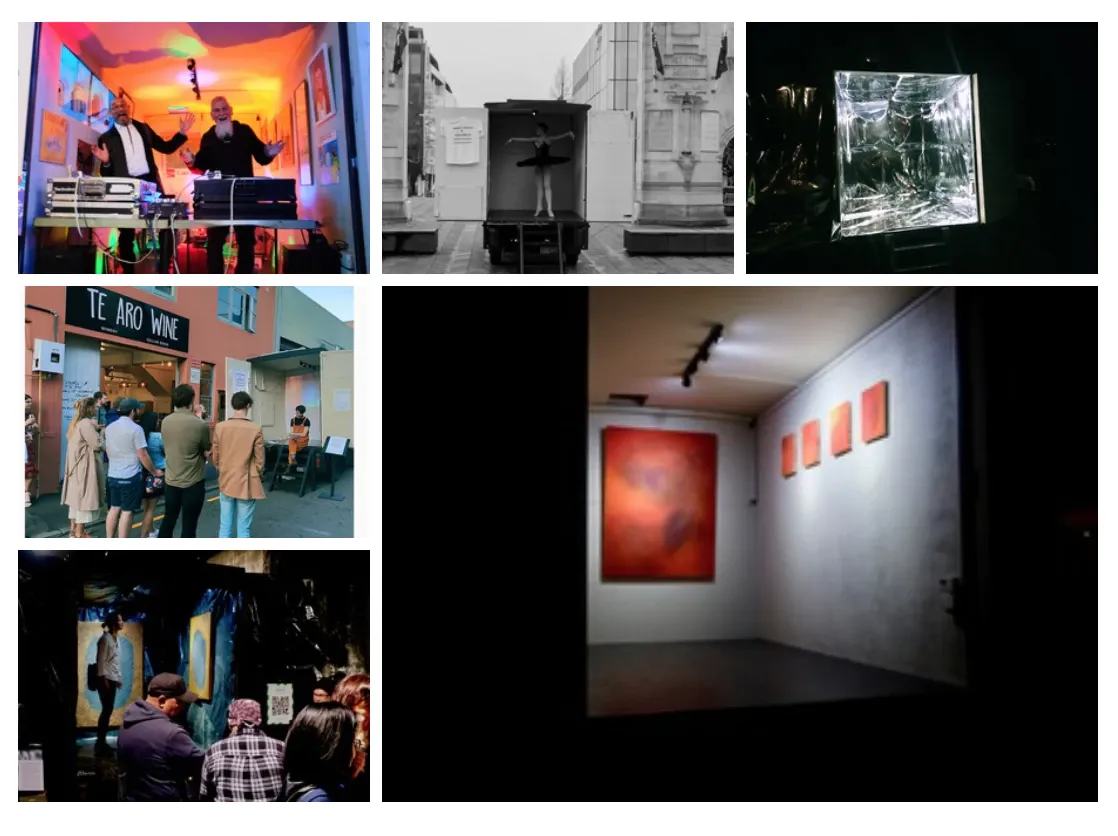

This is the story - to date - of an out-of-the-box independent public art project that began in Aotearoa in 2020 and now finds itself both in Belgium and Waiheke Island’s Connells Bay Sculpture Park.

It’s a story that crossed New Zealand throughout that revolutionary year, over two lockdowns, involving 100s of artists and was ultimately emblematic, in its response to the conditions, of these strange times. And it’s about to get a new chapter.

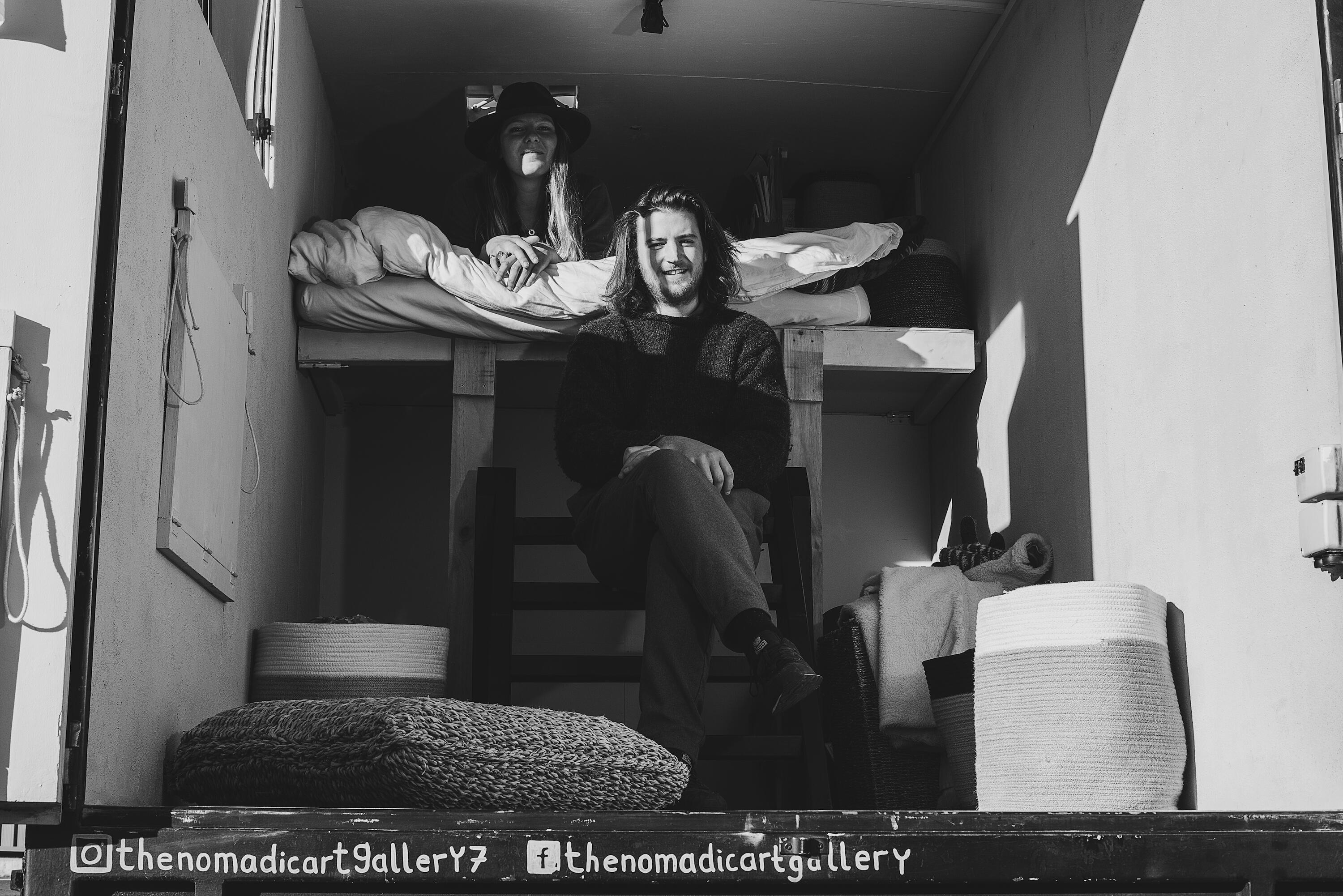

The Nomadic Art Gallery began as a small truck operating as a mobile exhibition space, office and home, while its exterior progressively got covered in art by 106 artists, from Tāmaki Makaurau to Ōtepoti. 16 exhibitions were held inside, and a bold new private art collection created for the Gardner family’s home on Waiheke Island. All curated and ‘driven’ by a visiting young couple from Belgium, Arthur Buerms and Eugénie Coche, passionate about art and its role in people’s lives.

All between January and December 2020, becalmed by two lockdowns.

Looking back on it, it does feel like a story of its times: border shutdowns, travel and personal distancing restrictions, new forms of community building, and the evolution of new relationships to our country and the world beyond.

It even offers reflection, Nomadland like, on the expense of housing and offers some kind of symbolic punctuation mark on rampant growth in international tourism and art world globalisation.

Art as freedom camping, connecting people together locally when we needed it most.

Two countries, one connection

In December, Buerms and Coche returned to Belgium, leaving their truck on public display with John and Jo Gow at Waiheke Island’s Connell Bay Sculpture Park. A month earlier, I joined them, a big bunch of artists from around the country and the truck at a remote bay on the island to launch the impressive Gardner collection of 82 works, after the couple had worked with little known and well-known artists nationally alike.

Having met them early in the year as an arts journalist, prior to lockdown, I was staggered by their perseverance, and the knowledge and community gathered. Applying the free energy of the young traveller with a focus, criticality met a love of meeting people and instincts for finding good work. Working so on-the-ground and fresh to the country saw them create their own map, breaking all sorts of invisible boundaries about who is in the centre of the art world and who is not.

In September this year, the gallery will open again, but in 160 square metres spread over three floors of a building currently lying vacant in Leuven, Belgium. Quite different to the m2 of their truck.

Photo: PH Photographie.

Reflecting where they now find themselves, with COVID still an ongoing concern, there will be exhibitions every six weeks featuring a New Zealand artist and a Belgium artist. A website will feature a different online exhibition by a NZ artist every six weeks. They anticipate the physical space being open for a year, and are already planning their next large-scale mobile nomadic public enterprise - keeping tight-lipped on what country and which mode of transport it will involve. Like the evolution of their project in Aotearoa, their new space without wheels has evolved they say quite organically - unplanned but open to opportunities.

“It was such a unique position we found ourselves in last year,” says Buerms, “to meet so many artists and be able to get a holistic vision of what is happening in NZ art. So with this space (in Belgium) becoming available and not being able to move, we decided to take the Nomadic Art Gallery off the road for a year. A sort of transitional art gallery”.

“To be a bridge between New Zealand and Europe,” adds Coche, “and to showcase artists that we met and art we enjoyed that we think Europe should see. It’s the perfect thing to do right now in realising our promise to all the artists we met.”

Who will be shown is still under wraps, but will also include artists they didn’t get to meet in person. The truck project was notable for its eclecticism and the way it spoke to our Pacific situation. In Leuven, there will be well-known names but, like the truck, “constant surprises”.

“We really want to keep the spirit of what we did,” Coche says. “To not be guided by any institutions but rather our fresh eyes.”

“Right now, we are not politically or financially tied to New Zealand in any way,” Buerms expands, “so that gives a lot of freedom in choosing and building partnerships.”

Interesting times for such a project - right now the ability for NZ artists to visit doesn’t look likely, yet the gallery can still allow people to see work from a country as far away from Belgium as possible.

Our story can travel through art.

Nomadic origins

Before and after. Photo: Supplied.

When the Nomadic Art Gallery began in January last year, there may have been no plan, but there was lots of research. The couple had spreadsheets of artists, and a clear sense of what they didn’t want it to be - “like a gypsy caravan driving around putting things in the back of the truck.”

So instead, they created an overarching concept and structure, to provide some kind of rigorous constraint, and be able to consider different artists.

They selected ‘Life’ as an overarching theme, with each exhibition taking different aspects. It began at the Lake House Arts Centre in Auckland with ‘Birth’ and ended back in Auckland with ‘Death’. In between, everything from ‘Love’ and ‘Alienation’ to ‘Nostalgia’ and ‘Belief’.

Little connections with people led them to other interesting people and artists and allowed “the dominoes to fall,” says Buerms. “As we went along more and more artists wanted to get involved and after a while it really started rolling.”

Arthur Buerms and Eugénie Coche. Photo: Supplied.

One thing was very evident from early on: as independent curators, Nomadic were prolific social media users, documenting the work of artists, disseminating their work and writing on their work online. Coming from the other side of the world, sharing their work and travels, no doubt helped push this, as did COVID. As public art curators, introducing a wide audience to new ideas was treated as an important component.

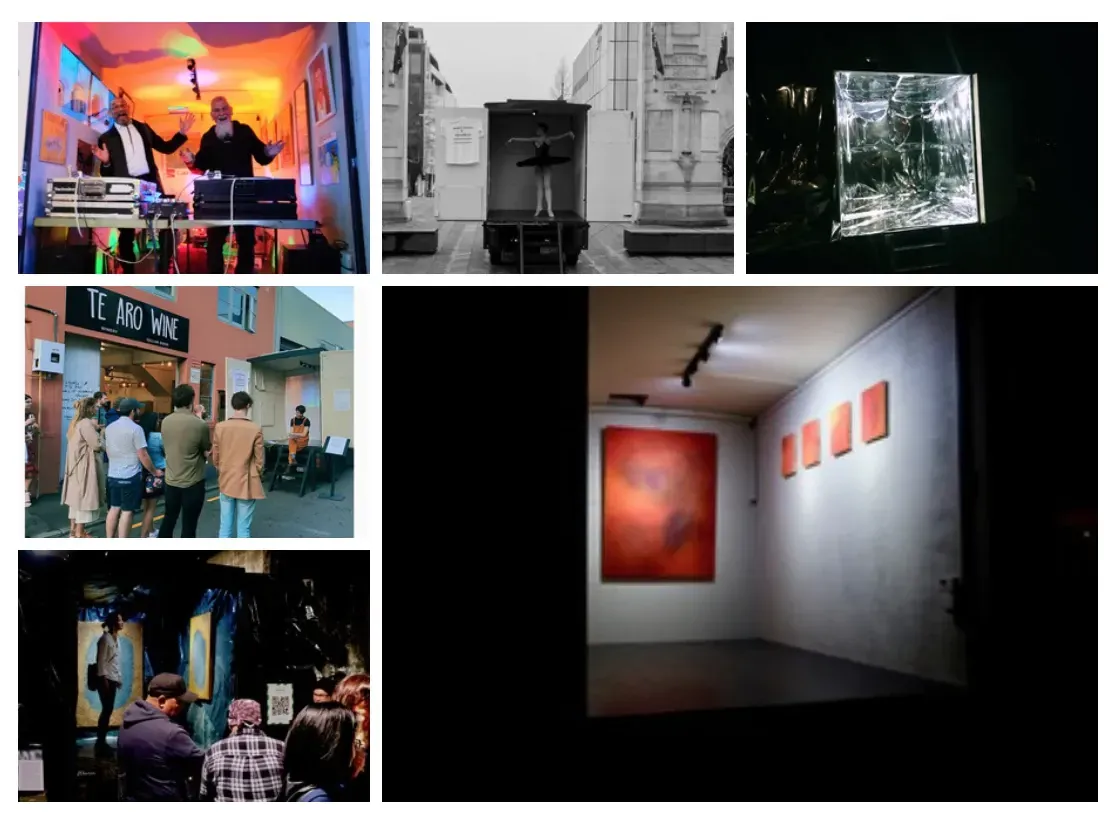

“We mostly wanted to work with spaces that weren’t really related to art in the financial sense,” says Coche. “Because of COVID as well we wanted to work with spaces that had less people coming to them. We worked with wineries or with the Blue Oyster Project Space in Dunedin - that was the only artist-run space we collaborated with - and with community art spaces like Corbans Estate in Auckland.”

“We loved to work with festivals,” says Buerms. “That was something special we could do, like the Hamilton Gardens Art Festival and Pride Parade. We did large-scale events where people didn’t expect to see a gallery.”

Countless contributors

Sometimes the surprise offered was parking up the truck for staging interventions, in unlikely contexts. For ‘Belief’ at Smash Palace in Christchurch, Tjalling De Vries and Luke Shaw transformed the truck into an enclosed audiovisual installation cum soundbox. In the same series, they were at Riverside Markets and the Bridge of Remembrance with a ballerina slowly making her way to the truck. In Nelson, Lee Woodman wrapped the whole truck in Milar (a polyester film) and the truck was parked in different sites broadcasting music.

Photo: Supplied.

When I saw the truck on the Wellington waterfront - an exhibition of woven photographic works by The Hori, including comment on cultural appropriation and the high Māori imprisonment rate - it was working well as a more conventional small exhibition space, open to the harbour, but one which at that time had multiple artists painting on the outside.

Contrast that to their very first show at the Lake House Arts Centre, with Ada Leung and Minrui Yang, where the truck, still white inside and out had its possibilities expanded physically as external and internal installation space, with calligraphic projections, work hanging flapping from the roof, covering the window, coming in through a sky-hatch and snaking out as umbilical cord onto the lawn. This was a gallery coming out of the womb.

The size of the truck and their intimacy with it meant Buerms and Coche had the control to easily learn how to change the space around, and extend its potential beyond expectations.

“We always wanted to reinvent the space and surprise people with a new interpretation of what the truck can be,” she says.

“The truck was such a small space but actually offered infinite possibilities.”

True freedom

The success of their project lies in a dual on-the-road openness to opportunity and the new - as well as a rigour that’s testament to their backgrounds in arts, law and project management. With time limited, they made a call to focus mostly on major centres, where they knew there’d be a concentration of artists.

Ironically that meant unlike other freedom campers there wasn't time for Fiordland or the west coast. But time well spent in the South Island is evident by the number of artists this project brings to the attention of those in the North.

“Just before the first lockdown hit,” says Coche, “we knew we might not have the chance to go to the South Island, so we drove the whole way from Auckland to catch the very last ferry! We also knew we had more chance of meeting artists if we went to where they were concentrated.”

The first lockdown was spent in Mapua near Nelson, and the second Auckland lockdown on the west coast at Karekare. But even then, those breaks were busy with building their website and hosting online exhibitions. Under other COVID levels, the smallness of the truck meant they could still be open, letting people in intimate groups in.

Photo: Supplied.

It was as if the project had been made for a pandemic.

“Sometimes now as I organise exhibitions for the new space trying to sort out a programme,” says Buerms. “I’m baffled how we actually managed to organise 16 exhibitions in places we didn’t know, living out of a truck. We were on a lot of adrenalin I guess!

“Because, at the same time artists were painting the outside. It’s like we never stopped - from 8 in the morning until 11. But we did see some amazing scenery - New Zealand was our office. Every city was our place, our home, our family.”

“The project was our life,” adds Coche. “We were on the move all the time because we knew we only had one chance. We could not miss one opportunity to meet with an artist.

“We would go to sleep with it - in the artwork itself. We were breathing our project - and maybe that’s what made it happen. We were driven more by our art than our travels.”

What the truck?

Photo: Supplied.

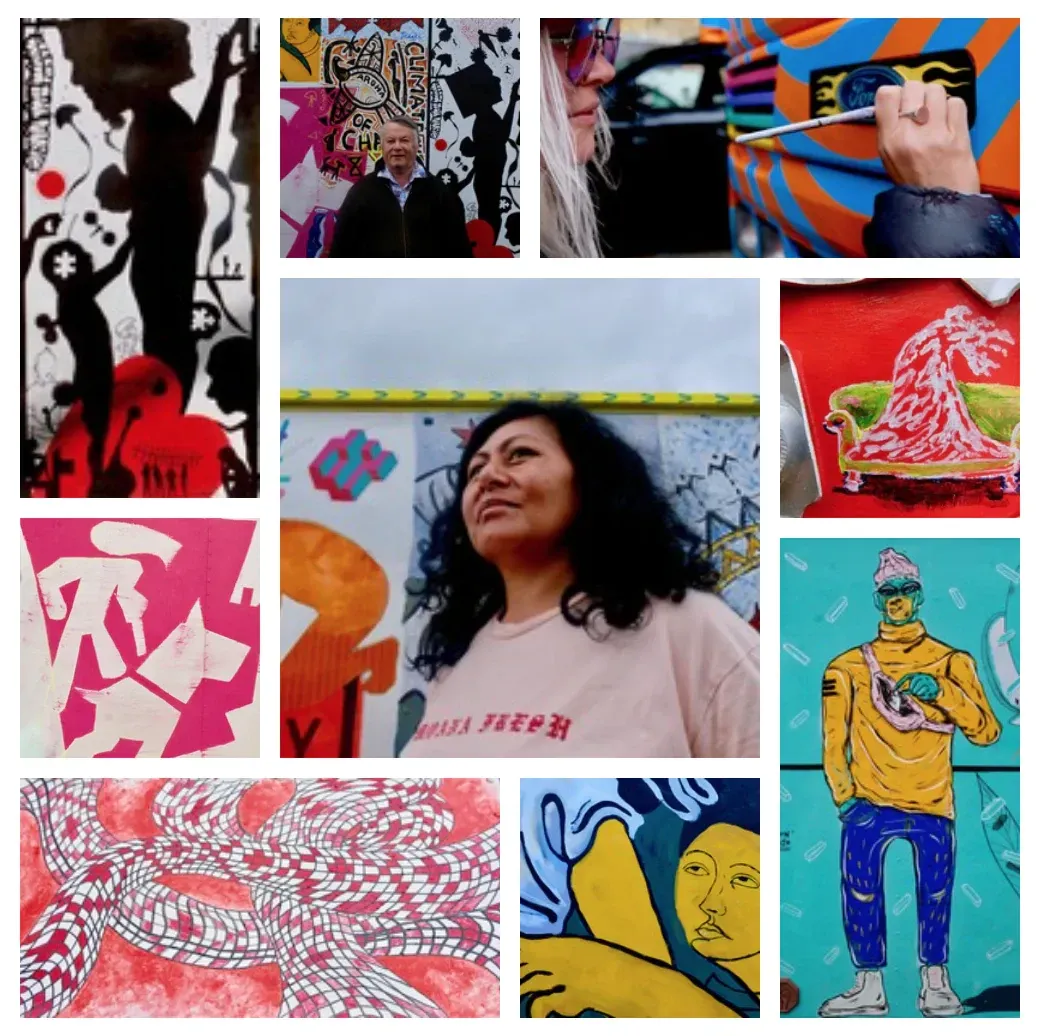

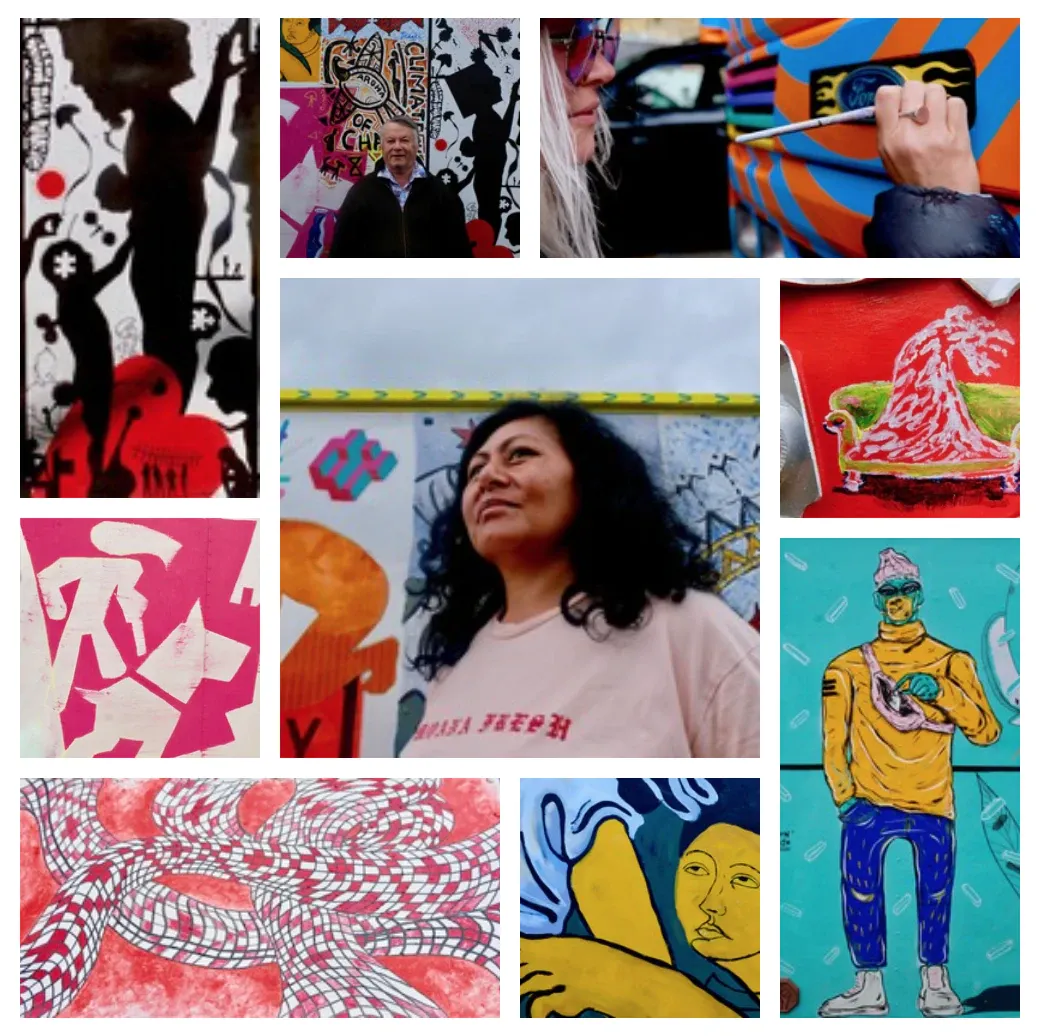

The collective covering of the exterior of the truck by some 106 artists is of itself an interesting project (archived on their website), recognised by its inclusion at Connells Bay Sculpture Park.

The first artist to paint on the sides was much loved Samoan Aotearoa painter Andy Leleisi’uao, who the pair met just prior to arriving in Aotearoa in Rarotonga while working at Bergman Gallery. “He took a bit of the role of godfather (for the project),” Buerms comments, “he opened the door.”

Leleisi’uao took a corner near the cab, his bold hallmark silhouette graphic style with elegant lines presented an elder and child, giant red heart at their feet growing up and outwards.

Whilst again open to artists stepping forward, they were selected from research quite carefully to map a broad range of visual languages - selecting artists with strong visual identities.

Other well-known artists like Nigel Brown, Fatu Feu’u, Scott Eady, Delicia Sampero and Philip Trustrum can be found on the sides. Yet equally I discovered many interesting new artists care of Nomadic’s curation.

When the van stopped off in the main street of my hometown of Paekākāriki, I arranged a great local artist Rachel Benefield to do a wee cartoon - two local penguins and a crab in conversation. In Dunedin, emerging artist Ana Teofilo added in Pacific greens and blues a large pattern reminiscent of Samoan siapo or tapa, but with beading she relates to Aboriginal artmaking.

Naturally, a fair few street artists add their bright patterning, but often with their experience on the more difficult surfaces: Dunedin’s Aroha Novak with a bright poutama tukutuku pattern on the sides of the cab; Wellington’s Mica Still across the front, Dunedin’s Claire Rye on some of the hubcaps and nomad D-Side takes on the exterior roof. Shannon Novak breaks up light and asserts gender and sexual diversity, with a rainbow flag vinyl work across the sole small gallery window

Then there are small touches to look out for: Dunedin’s Sarah Dolby provides a delightful two-sided small painting to hang spinning below the rear view mirror, Christchurch painter Marie Le Lievre paints the interior roof of the cab and Dunedin’s Harry Freeth has drawn a fake vehicle registration for inside the windshield. In two sculptural additions, Auckland’s Levi Hawken has created a terracotta version of a Black Lives Matter badge and Natanahira Te Pona a carved wooden tekoteko.

The brief to artists was kept deliberately open, leaving the more academically trained artists Buerms thinks more inclined to think about what the truck stands for or means.

Photo: Supplied.

“That was a funny question.... The truck stands for so much. Not only as a universal sign of unity and connection but also as a reflection of its time - of authorship and individuality. Whether art can exist independently of its context and its environment - and how it is perceived by people outside the professional art world. If it’s in a car park outside Countdown, is it perceived as having less value? 99% of the time that will be true. For a lot of the artists, they are asking ‘What will other artists think? Or, what will my gallery think?!’ It makes us think about the social mechanisms in the art world.”

These works individually are modest in ambition and within their artists’ practices, made for hard weathering - no one would argue otherwise- but what counts is the community that the project gathers - the value it places on diverse creative expression in the eye of an isolating pandemic. Buerms and Coche are also keyed into how their entire project speaks to social issues.

“People our age often cannot afford to live in a house anymore,” says Buerms. “With a van, you can make it really comfortable and have a rich life with connections with people.”

At Connells Bay Sculpture Park the truck is, currently (have truck, can travel), the third sculpture you encounter, sitting on the flat in a wee nook surrounded by lush native bush. You can go inside, where the couple’s bed is now folded down, speaking to its other important use.

“Soon it will need to go inside, because we need to keep the work protected so it can be an ongoing performance and even tour, nationally or internationally. We will invite artists to keep touching up their work. Because for us it’s really a family - artists who have taken risks with us, people who have invited us into their homes. ”

“It really is,” adds Coche, “a moment that we have shared…. Say hi to New Zealand for us!”